Sonia Rykiel

September 18, 2016“I don’t know if I’m perceived as being provocative. I suppose it’s an attitude that I’ve had since Day One. I am not swayed by anybody else. Who cares what they think?” Sonia Rykiel. The influential fashion designer Sonia Rykiel has died aged 86. Her influence on fashion was in helping to create the gamine 1960s girl, and an enduring image of the sexy, intellectual left Bank Parisienne.

Sonia Rykiel, 2009.

nicogenin, CC BY-SA 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

They would be casually dressed in one of her “poor boy sweaters” which looked like an ineffable part of that artlessly thrown together brand of French chic yet which nevertheless took a long time of Rykiel to perfect with the result of emphasising a tiny, graceful body to perfection. Sonia Rykiel has been called a 1960s version of Coco Chanel, bring back her ideas of comfortable, unrestrictive knitwear for women back in a modern guise.

Not only that but in her native France, Sonia was not just a fashion designer but an intellectual, an author and philosopher, writing several books including erotic ones.

Sonia Rykiel was known as the Queen of Knitwear though she had never picked up a pair of knitting needles. Instead, she was the type of designer who simply knew exactly what effect she wanted, and relied on others, in this case the knitwear technicians at her husband’s factory, to work out exactly how to get it.

Sonia Rykiel – Wife and Mother

She was born Sonia Flis in Neuilly-sur-Seine, France, in 1930, the oldest of five daughters. At the age of 17 she was employed as a window dresser in a grand Parisian department store, but on her marriage five years later to Sam Rykiel, she stopped work to become a Sonia Rykiel – wife and mother. Her childhood dream was to get married and have children.

Sonia Rykiel – tentative designer

1986 Spring-Summer knit set by Sonia Rykiel, Paris.

Staff photographer, Rhode Island School of Design Museum of Art, CC0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sam Rykiel owned a clothing boutique in Paris called Laura, and later, while pregnant in 1962, Sonia approached one of his suppliers, an Italian knitwear company, to make her something that she was happy to wear. “All the clothes were very sad,” she said. “So I made a dress that was bigger, fuller, more gay.” Naturally very thin framed, she wanted a sweater dress that would cling to the body, with very small, high armholes and tight sleeves. After seven attempts it was perfect and the way the skinny rib, stripy jumper clung to her bump at a time when maternity wear was more all-enveloping sheet than revealing chic scandalised her mother in law but pleased a lot of other young mothers-to-be, leading to the design being stocked in the Laura boutique as both pregnancy and non pregnancy wear.

And after the pregnancy she wanted a post pregnancy version, and had a sweater made along the same lines. A journalist from Elle Magazine saw the jumper and loved it and a red and pink version was modelled by Francois Hardy on the cover in 1963. Audrey Hepburn was a fan; so were Brigitte Bardot, Catherine Deneuve, the Countess Jacqueline de Ribes, and Claude Pompidou.

Rykiel began designing other items of knitwear for the boutique, initially under its own Laura label. Her personal look, with a fluffy, flaming red bob and circles of dark eyeliner made her a great brand ambassador.

Sonia Rykiel – the boutique

Bowler hats by Sonia Rykiel in Paris 2008.

THOR, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

By 1968 Rykiel was able to open her own boutique and design under her own label. Her clothes were still knitwear based, but in the style that was being experimented with at the time known as “la demode” – anti-fashion. So they were unstructured, unlined, un-hemmed; predominantly made with jaunty stripes and sometimes with words and slogans, or knitted bows and ruffles. Her knitted dresses came in different fabrics like mohair or angora, and to go with them there were brightly coloured fun-fur jackets, rhinestone embellished berets and classic French trench coats.

She claimed that black was her signature colour – “the colour of philosophers” and of course, the colour that set her own shock of hair off best, but actually her collections were as likely to come in fuchsia pink paired with hot orange, or electric blue paired with just the right tone of beige to make it pop. If she was passing by and saw a colour she liked, on a wall or parasol for example, she would snip or chip a bit off and carry it off to have it matched by her factories. She was also unafraid of using the same shade twice if she liked it – a particular shade of blue was to re-appear on and off throughout her entire career.

Sonia Rykiel – the designer who designed for herself

Clothing, 2008.

THOR, CC BY 2.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Sonia Rykiel was a designer who made clothes that she herself wanted to wear, quite literally designing herself a coat if she felt cold, and if she felt that her mood demanded a trench coat, a trench coat it would be. If she felt a bit more exhibitionist that day, it would be the big bright fun fur coat. Her own explanation was more abstract: “I am typically and ideally the kind of woman I want to make things for – women who move, women who travel, women who live even with difficulty, women who have children, women who have men, women who feel sad, women who play.”

These women, she insisted, need not be physically like her: “it’s not true that clothes look better on skinny girls – what counts is the attitude. A woman must have a philosophy as well as all the rest. It hasn’t been important to put a woman in a blue dress. I wanted to dress women who wanted to look at themselves. To stand out. To be women who were not part of the crowd. A woman who fights and advances.” She proved her mettle by signing the infamous “Manifeste des 343 Salopes,” (Manifesto of 343 Sluts), a declaration written by Simone de Beauvoir in 1971 which was signed by 343 women who had had an illegal abortion.

This philosophy translated as clothes that were both comfortable and sexy.

She expected her models to be expressive, instructing them to look like they were having fun on a catwalk, not to look so serious and sullen as norms dictated.

Sonia Rykiel – a flourishing business

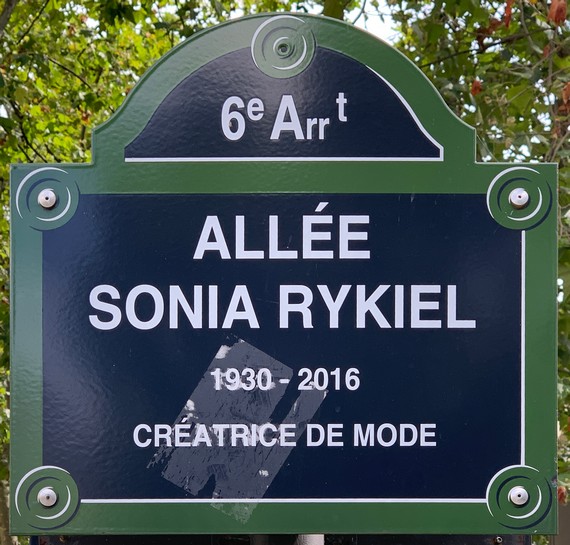

Plaque – Paris VI.

Chabe01, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

Unfortunately for her childhood dreams of becoming a good housewife, as the business flourished her marriage faltered ad she was divorced. Her daughter, Natalie, joined the firm in 1975 proving that she was a great and inspiring mother, however. (She also had a son named Jean-Phillipe). Nathalie helped her to branch out into other ventures, including mens and children’s wear, fragrances, china-ware and chocolates and redecorating international hotel chains.

Sonia Rykiel – an author

Sonia Rykiel ‘s books included an A to Z of fashion, a collection of children’s stories, and novels such as Casanova was a Woman which has three characters: a man, a woman, and a sweater. Not surprisingly for someone with such strong opinions on women, fashion, children and life in general she set them down in a book, Et je la voudrais nue (And I Would Like Her Naked). Her boutique on the Left Bank was full of books, not just coffee table tomes about fashion but novels and thought provoking essays.

Her final book was in 2012 when she wrote about her Parkinson’s disease in collaboration with Judith Perrignon. N’oubliez pas que je joue (Don’t Forget It’s A Game) was written with her typical insouciant wit and honesty, although she revealed that the disease was a painful one for her sense of self: “I don’t want to show my pain. I resisted, I hesitated, I tried to be invisible, to pretend that nothing was wrong. It’s impossible, it’s not like me.” She also said that colleagues stopped her from being photographed with her cane, an aide she had been relying on for several years.

The muse

Sonia Rykiel was not only an artist but a muse too – Karl Lagerfeld made dozens of portrait sketches of her, and her fierce look was captured by Jean Cocteau and Andy Warhol.

Her character was captured on film as she was the inspiration for the lead character in Robert Altman’s film Prêt-à-porter, (1994) where she also appeared as herself. Also in 1994 she recorded a duet with Malcolm McLaren entitled Who the Hell is Sonia Rykiel?

It was an obviously ironic title as by then, everybody knew who the hell Sonia Rykiel was. She was a grande Dame of French couture, and was recognised as such in 2008 when she was awarded the Commandeur of the Légion d’Honneur by President Sarkozy. She didn’t, however, mince words about the experience: “Sarkozy got there very late, read out a piece of paper that had no doubt been dictated to him by someone else, thanking me for having worked hard for France, and that was it.’’

France showered more honours upon her, making her a Commandeur de l’Ordre des Arts et des Lettres in 2012 and in 2013 a Grand Officer of the National Order of Merit.

The future of the business

Although Rykiel had always remained as the figurehead of the business, Nathalie came to take over the day to day running and is still the managing and artistic director of the label, whilst Julie de Libran, an accomplished designer who has worked for Marc Jacobs amongst others is now head of design.