The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock

December 20, 2015Imogen Hermes Gowar is one of my favourite writers, whose novel, The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock, contains plenty about women’s fashions and lives in the 18th century. I was delighted that she had time to go into detail with me about pins and pigs.

Part One of the interview can be found here.

GJ: How integral to the plot is a character’s appearance and what they wear? For example, in the excerpt of The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock I’ve read you vividly describe a man’s haircut and I think this says a lot about him. Tell me about some of the other characters, did you base what they wore on real portraits or contemporary descriptions of clothing?

IHG: My main female character, Angelica, does quite a lot of dressing and undressing. She’s a courtesan so the way she looks is really important, but in fact the sensuality of clothes was often seen at the time as a reason women became prostitutes. There were plenty of contemporary anecdotes of girls who were coerced into sex for velvet ribbons and trimmings – Emma Donoghue’s Slammerkin addresses this a bit further. In her memoir, Mary ‘Perdita’ Robinson (an actress and onetime mistress of the Prince of Wales, who later became a writer) describes her outfits as she goes along – ‘I wore a dark claret-coloured riding habit, with a white beaver hat and feathers’ – and for her, fine clothes were a sign of arrival, after a childhood of not being able to afford nice things.

![Jacques-Louis David [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons Jacques-Louis David [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons](https://upload.wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/5/50/Jacques-Louis_David_-_Anne-Marie-Louise_Th%C3%A9lusson%2C_Comtesse_de_Sorcy_-_WGA06063.jpg)

Jacques-Louis David [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons

I like the quite mannish tailored redingotes, but it must have been a revelation when the white muslin chemise a la reine (also called the Perdita Gown, after the trendsetting Mary Robinson) became fashionable in the 1780s: it was so simple and light to wear; it fastened with drawstrings and you didn’t need loads of heavy petticoats or bulky hoops. Women must have felt amazingly unencumbered, but also quite exposed without recourse to extravagant, imposing gowns and towering hairpieces.

One of the criticisms of the chemise a la reine was that it was so plain you couldn’t tell the class of the woman wearing it. That was a mentality I found quite interesting, given the huge social flux that existed at the end of the eighteenth century: the boundaries between classes became very permeable as industrialists started making big money, and it wasn’t uncommon for tradespeople to marry into the gentry, and vice versa.

For my research into clothes, I used the internet a lot. There is a huge community of Georgian fashion buffs out there, often with PhDs, who were very generous with their information about how dresses were made and worn, how hair was curled, all that stuff. Their knowledge is incredible.

I don’t think any of my characters can be traced back to specific portraits, but I did make a Pinterest board… there is a 1780s look of big, powdered curls, broad-brimmed hats, and very black eyebrows, which is fabulously striking and probably due a comeback. I don’t think I could have written this world without loving the fashion.

GJ: Are there any historical leftovers as it were, any little tidbits that you wish you could have got into The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock somehow but had to sadly leave out? If so, hit me with a cool Regency factoid!

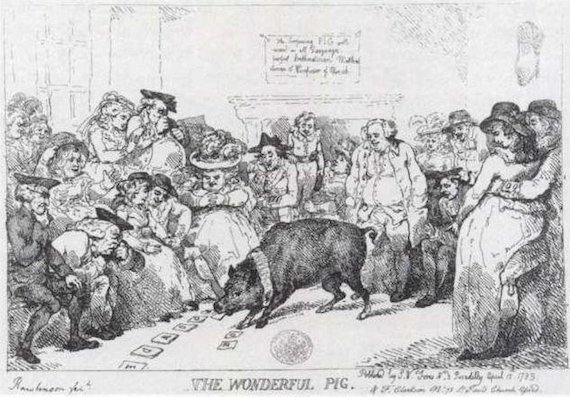

IHG: I tried to curate all my favourite Georgian things into The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock but some things didn’t make it. The Learned Pig was a delight of mine: it could do sums and tell people’s fortune, and took London by storm in the mid 1780s.

I also wish to raise awareness of how important pins were in the 18th century. You used them for everything, and particularly for fastening clothes, so when you got undressed to had to pick out a lot of steel pins. Most women kept a little box on them at all times. Recently quite a lot was made of how Jane Austen edited her novels with pins, as if that were a very domestic and female thing to do, but in fact clerks did this with documents all the time. It was perfectly professional. In offices, pins were kept on strips of paper, coiled up like a Chelsea bun.

Finally, a tip for anybody who wants to do the research. There was a black woman, I think named Mrs Lewis, who arrived in London from Jamaica after her white lover died, and went on to run an all-black brothel. I’ve only found a few disparate mentions of her, but often people assume that historical material doesn’t exist until they actually start looking for it, so I don’t think it’s a lost cause. A lot more work needs to be done on Black Georgians, because they certainly existed, and I’d love to know more about her. Particularly whether she was serving a black community.

***

Imogen has already won the Curtis Brown Prize for a part of this novel, and is now shortlisted for the prestigious Mslexia First Novel Award. She has also won the Malcolm Bradbury Memorial Scholarship at UEA. If you missed it, Part One of our interview with Imogen is here.

Follow Imogen on Twitter on @girlhermes and @covgardenladies . And, for a tantalising extract of her novel, The Mermaid and Mrs Hancock, check here.